In many ways, this post is about whether I, as a strategist, would make a slide recommending union-busting. Slides are the norm in business communication and strategy making from the C-Suite on down. And I often wonder about how I would respond to different situations in that context.

Personally, I have no direct professional experience with unions. And I don’t remember any detailed union conversations in my various strategy training sessions over the years. The historically low unionization rate in the United States[1] and/or my lack of work in union-heavy companies could be the main reason for this. Strategists who work in more unionized industries may have their approaches and opinions set on the topic. Even though I’m pro-union, my lack of direct experience allows me to think freely about how I would respond to unionization while forming a strategy.

With unions covered in the news more frequently, I can see the issue re-entering the strategy room if it hasn’t already. The recent resurgence of unions has led to more union busting activities.[2] But that doesn’t mean I would recommend union busting as a part of strategy work. To determine whether I would write a “union-busting slide”, would require knowing the real strategic implications from union activity.

To that end, we’ll look, briefly and on a high level, at what unions do and what their trajectory has been in the United States. We’ll then properly categorize strategic issues from unions and discuss potential strategy responses. In the end, we’ll see if I would write the union-busting slide or not and what that potentially says about me.

What do unions do and Where did they go

Simply put, unions represent workers’ interests to management. Unions have been credited with safer working conditions, ending child labor, the 40-hour work week, the weekend, and other pay and working condition improvements.[3] The unions accomplish this through organizing workers, collectively bargaining, and lobbying for legislation.

Union strength is based in a few key areas (and probably more). First and foremost is membership level. A high number of unionized workers levels the negotiation playing field with management and adds strength to strikes and threats of worker slowdown. Second, labor laws can strengthen organizing, reinforce collective bargaining, and codify key union and worker priorities. Third, unions get stronger from having a clear problem to solve. If union priorities are proactively adopted by employers or codified, then the union might have less to do. However, with the ever-changing dynamics around the future of work and the holes in the U.S. social safety net, I’m not too concerned about the unions running out of things to do anytime soon. Lastly, public sentiment can drastically add to and take away from union strength. If the unions are viewed as having a strong and effective purpose by the general public, then politicians and employers will move in their favor and vice versa.

In the 1950s, unions hit peak membership when “1/3rd of all employees belonged to a union.”[4] Today, that number is 10.3%.[5] This decline is due to a long list of reasons, including:

- Decline in various legal protections for union activities and pro-employer legal changes, like right-to-work laws

- Key union positions either being codified into law or adopted as standard by employers like the minimum wage, health benefits, etc.

- Strong decline in public sentiment, with union approval dropping from a high of 75% to 55% between 1953 and 1981, which was paired with a +19 point uptick in union disapproval over the same time period[6]

- Globalization and free trade starting in the 1970s also decreased the U.S. manufacturing base, a traditional union stronghold, with a commensurate lack of unionization in industries with growing employment[7]

Precise explanations of each reason are intricate, detailed, and address long-standing cultural legacies, but are too vast for the scope of this article. Suffice it to say, the unions have taken hits over time and, while remaining a force in key industries and in the public sector, have not returned to their prior prominence.

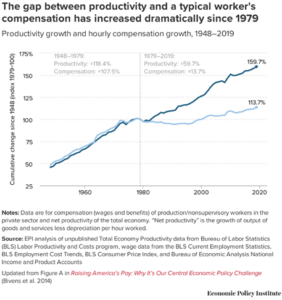

Union decline is tightly related with three data points. First is the break between wage growth and productivity growth that started in the 1980s[8]:

A study has shown that minimum wage, which is $7.25/hour today, would be $26 per hour if it had been changed to keep up with productivity.[9]

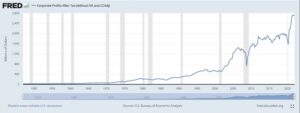

Next is the increase in corporate profits after tax[10]:

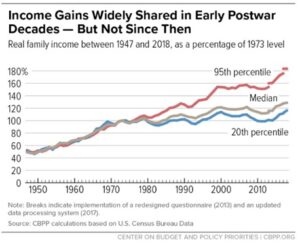

I fully recognize that there are several factors that have impacted profitability over time. However, this change in relation in the next data point is hard to ignore[11]:

Income or wealth inequality is a story often told alongside the union decline with multiple data points to highlight the problem. The Rand Corporation has estimated that the upward transfer of wealth from 1975- to early 2020 is equal to 50 trillion (with a “t”) dollars.[12]

There is certainly a lot more to this data. Explaining long term trends requires looking at a lot of factors. However, it is hard to look at those three charts, especially the first and last chart, and not also conclude that union decline is a strong contributing factor to the rise of income inequality. A union’s main purpose is to ensure positive wage, benefit, and conditions growth that tracks with a company’s growth. It is not a huge leap to conclude that this is the result of life without unions.

While this background is helpful, it is not the full story for strategy work. The ongoing pandemic, an uptick in union approval to 68%[13], the return of manufacturing jobs, union expansion into tech and service sectors, and increased organizing activity might be the spark that brings unions back. If the government provides further protections via the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, then this could be a pivotal point in U.S. history where the unions become more of the norm once again. If that happens, then history alone won’t guide me on what to do with my union-busting slide. For that, I’ll need to dig a little deeper.

So what is a strategist to do? . . .

Despite the many political and philosophical perspectives, we try not to get too political in the strategy room. Strategy output is inherently political within a company’s structure, but I’ve never gotten the sense that it should be political externally. As we’ll see next, we aren’t always as insulated as we want to be. In an attempt to remain intellectually honest, we should assess the strategic presence unions have.

What I Would Do

In my strategy work, I assess what will impact the company’s market position and its ability to maintain it. I ascribe to a common point of view that industries contain a finite number of strategic positions, and companies will occupy and operate at different positions. The company’s market position inherently determines company size and profitability. The number of available profitable positions and competitive intensity will be dictated by the various industry factors and dynamics. This is largely in line with views pushed by Michael Porter (though in fairness and transparency I don’t know his view on unions). There is certainly a lot more depth to it. But, simply put, I won’t really address anything in strategy work that falls outside of this framework, unless it leads to a socially bad decision.

Cutting to the chase here, I haven’t found a strategic disadvantage from mere union existence and activity. I can feel people looking at me weird through the computer somehow. That’s because it has been a long-standing narrative that unions cause competitive inflexibility, especially with overseas competition, and eats so much into profits that businesses can’t survive. But this appears to be just a narrative.

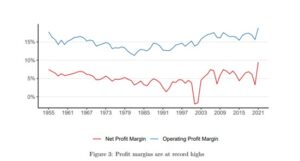

One piece of evidence for this is the relatively steady corporate margins during both the union’s height and decline. The Roosevelt Institute examined this issue and produced the chart below[14]:

While there are ups and downs in the data, which I would expect in business cycles generally, I don’t see wholesale threats to margin at any time. In fact, it looks like operating profit margin was pretty good at the height of union strength. If you make the right choices with those margins, then you can maintain growing and profitable positions.

In 2003, Princeton, then-UC Berkley, economics professor David S. Lee and the late University of Michigan Prof. John DiNardo wrote a paper further supporting this thinking. The two economists used data from over “27,000 establishments that faced organizing drives” between 1983 and 1999.[15] In their words, “The analysis yields a surprising result: little or no union effect on business dislocation rates over 1- to 18- year horizons.”[16] And they are not the only ones who came to this conclusion either.[17] The charts earlier in this post support this as well. If the maximum impact a union has is to grow wages with productivity, then we should do well in general.

In that respect, unions become another industry force to manage like suppliers and buyers rather than an immediate existential threat to the company and its position. Like any industry force, whether benign or destructive, unions will only be a major problem if you are already strategically weak. And, if you are strategically weak, then more antagonistic threats like competition, declining consumer interest, and powerful suppliers should be top of mind. The union needs the company to survive, and, therefore, should actively work with the business on survival.

Because some of you might think anecdotal evidence gets equal weight in union conversations. You might say, “But Eastern Airlines got put out of business by a union strike.” Well, not really. For Eastern Airlines, it was more of a sense of “this was the last straw”. Here’s an excerpt from a New York Times article at the time titled, “Eastern Airlines Brought Down by a Strike So Bitter It Became a Crusade”[18]:

That’s a lot going on before and during the strike.

In the years prior, the Eastern Airline pilot, flight attendant, and machinist unions made “large concessions on wages and benefits” in return for stock and board seats. Later on new ownership, who sought to sell Eastern’s assets to help fund other airlines, destroyed union relations leading to a massive strike. The new ownership would try to break the strike with much cheaper replacement workers, but this raised safety concerns with customers and led to real mechanical issues. On top of losing consumer confidence, a bankruptcy court examiner found that the new ownership deprived Eastern of $280-400 million in self-dealing transactions to boost other airlines. Otherwise known as the exact issue that started the strike.

Industry consolidation after deregulation, oversubscribed on planes, increasing debt, increase in fuel prices, self-dealing leadership, and dropping consumer confidence seems like a lot of strategic issues to deal with. Just to put some timing on it, Eastern’s problems started with deregulation in 1979, the self-dealing leadership took over in 1986, and the strike began in early 1989, which was 5 years after major union concessions to keep the business going. Seems like un-caring and allegedly corrupt leadership took over a struggling business and proceeded to strip it in favor of other parts of their portfolio. How would this anecdote change my initial conclusion? Like I said, unions could only be bad if you are strategically weak, and Eastern Airlines was weak well before its labor relations deteriorated.

Personally, I work too hard as a strategist to leave any company I work with strategically weak. And the balance of the data points to unions not impacting company positioning or survival. Therefore, you won’t ever see a union-busting slide from me.

The Other Side Though . . .

Some strategists could write a union-busting slide. To do that you must subscribe to certain economic theories and business beliefs. On the economics side, Milton Friedman laid out the theoretical argument against unions[19], which gets repeated to this day.[20] From a strategy perspective, you’ll need to believe that shareholder primacy and profit maximization are the main purposes of corporate strategy.

This line of thinking, popularized since the 1970s, gained institutional heft when thinkers like Friedman gained fame and publicity, and consulting firms promoting value-based management and metrics began to pop up with the singular goal of maximizing shareholder return.[21] And remember, a union will always impact the stock price[22]:

With stock prices tied tightly to executive compensation, the union’s role in decreasing income inequality will literally take money out of the pocket of shareholders and management. Furthermore, a sinking stock price will put managerial jobs in jeopardy. Therefore, unions present a very specific money and corporate political problem to any company’s leadership. And, for a strategist who accepts shareholder primacy wholesale or wants to stay tight with corporate leaders who do, this is more than enough motivation to write the union-busting slide. But let’s be clear, this says more about the strategist and their beliefs than it does about a company’s strategic position and security.

Unions as Strategic Partners and Conclusion

There you have it. If you are positional in your strategic thinking, then there will be no union-busting slide. If you wish to promote or stay close to those promoting shareholder primacy and anti-union economic theory, then you will write the union-busting slide. It says more about the leadership and the strategists themselves than strategic implications.

But my conscience won’t let me leave it there entirely. While I don’t float “let’s run this race together” -type solutions often, we should give some thought about unions as a strategic partner. Arguably, even Eastern Airlines could have avoided its fate if it had stayed on the path of maintaining good labor relations. Even if its end was inevitable, it could have been delayed for a less worker and stability disruptive ending.

Management and unions rely on the existence and health of the company, which is directly impacted by strategic decision-making over time. The true status of a company’s health is logically a contentious issue at collective bargaining. And this tension can drive the strike and strike-breaking threats on each side. Therefore, I say that management should let the unions into the strategy making process.

We know that it remains unclear whether union presence alone cures this information asymmetry, and more than likely it doesn’t.[23] If we could cure this information asymmetry, then we could get better collective bargaining agreements for workers and the company. You could argue the fairness of the deals to Wall Street to mitigate negative stock price impacts, or the presence of sound strategy and good labor relations will lead to better gains over time (i.e., you might have to shelve your quarterly capitalism too).

Good and well supported strategists can play a role in this regardless of personal views or incentive. Theoretically, the strategy team can be used in at least three ways:

- Analyze the factors leading to unionization and addressing those factors fairly, honestly, and openly

- Engage with union leaders to develop a common strategic factbase for unions and management to act as a single source of truth

- Give meaningful analysis on the future of work and productivity to establish agreed upon projections

Strict confidentialities must be maintained with real consequences for both sides in case of breach. However, union participation in strategy formation and financial projections would also give union leaders a strong basis for effective membership communication and assessing negotiation priorities, which can further smooth out the collective bargaining process.

Unions could even hire their own strategy red teams to review the factbase and other work to gain further trust and deepen perspectives. The unions could also contribute strong frontline insights that could enhance company strategy overall. You might even spot market opportunities that weren’t visible from the C-Suite.

Admittingly, this is all theoretical and maybe idealistic. We would need more study, especially into available precedents, and more details to build on this idea. It also does not absolve the government from its role in ensuring good labor relations and social safety net as well. But, as a starting point, you must admit that recasting unions as a strategic partner could be very productive.

Sources:

[1] https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf

[2] https://time.com/6107676/labor-unions/ and https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/04/24/amazon-apple-google-union-busting/

[3] https://stacker.com/stories/2505/30-victories-workers-rights-won-organized-labor-over-years

[4] https://youtu.be/XWFocLnBdhM (MIT OpenCourseWare)

[5] See note 1.

[6] https://news.gallup.com/poll/12751/labor-unions.aspx

[7] https://www.cnbc.com/id/47323840

[8] https://www.epi.org/blog/growing-inequalities-reflecting-growing-employer-power-have-generated-a-productivity-pay-gap-since-1979-productivity-has-grown-3-5-times-as-much-as-pay-for-the-typical-worker/

[9] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/minimum-wage-26-dollars-economy-productivity/

[10] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CP

[11] https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality

[12] https://time.com/5888024/50-trillion-income-inequality-america/

[13] See note 5.

[14] https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/RI_PricesProfitsPower_202206.pdf

[15] https://www.princeton.edu/~davidlee/wp/unionbf.pdf

[16] See note 15.

[17] https://www.jstor.org/stable/2525061#metadata_info_tab_contents

[18] https://www.nytimes.com/1991/01/20/us/eastern-airlines-brought-down-by-a-strike-so-bitter-it-became-a-crusade.html

[19] https://youtu.be/EJEP7G7C0As (“Who Protects the Worker” Lecture in the Milton Friedman Speaks Series)

[20] https://www.heritage.org/jobs-and-labor/report/what-unions-do-how-labor-unions-affect-jobs-and-the-economy

[21] Kiechel, Walter. The Lords of Strategy: The Secret Intellectual History of the New Corporate World. First Edition, Harvard Business Review Press, 2010 at Chapter 12.

[22] https://time.com/6168898/why-companies-fight-unions/

[23] https://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3298&context=etd