Democratic losses can often be shocking and confusing. For example, in 2010, former Sen. Scott Brown shocked Democrats when he defeated former Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley for the late Sen. Ted Kennedy’s seat.[i] It was a surprise loss that endangered President Obama’s Affordable Care Act push.[ii] In another example, Democrats lost every toss-up U.S. House race in 2020 despite winning the U.S. Senate and Presidency, in a precursor to losing the House entirely in 2022.[iii]

Presidential losses are often the most shocking and confusing. Former Vice President Al Gore lost his home state and, quite controversially, the Florida recount to then Texas Governor George W. Bush despite President Clinton’s high approval ratings[iv] and winning the popular vote. Four years later, many Democrats believed former Sen. John Kerry should have won given the economic and foreign policy environment. But he lost, and Democrats were confused again.[v] Most recently, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton provided, hopefully, the shock of a lifetime by losing to Donald Trump despite winning the popular vote.[vi]

As a lifelong Democrat, I can distinctly remember the sting of each of the aforementioned losses, as well as countless others. Speaking personally, the general pattern always felt like: 1) Believe that we have the better ideas, 2) Believe we clearly communicated those ideas, 3) But then we let other, supposed, non-issues (i.e., who’s more likable, scandals, etc.) take hold in the election, 4) we lose, and 5) everyone tries to explain what happened and what Democrats should do next. I’ve ridden this roller coaster so many times that I don’t even scream anymore.

However, after being in business strategy for some years now, I’ve realized that this shouldn’t be the case. When a business fails, rises, or stagnates, you can eventually find some consensus about the strategic factors behind that outcome. But I bet if you ask 100 Democratic operatives today why John Kerry lost in 2004, you’ll get 100 different answers. This seems odd to me. While this post won’t be a total review of all Democratic losses to find patterns and consensus, I will transfer some of my business strategy approaches to develop a consistent framework for determining why Democrats lose. I’ll point out some helpful examples and data along the way and will be applying this framework to Stacey Abrams’ 2022 Gubernatorial Campaign in a later post. Until then, let’s take a step towards better understanding what goes wrong for Democratic candidates.

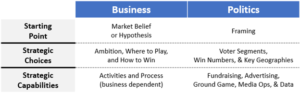

The General Business Framework and Translation to Politics:

The Business Part

The following is a brief, yet simplified, overview of business strategy formation. To form a business strategy, you first must develop a belief or thesis about the business landscape and how to extract value from it. This thesis establishes the outlook on and how you discuss the market. In a healthy strategy formation process, you will then test this thesis with rigorous data and industry analysis. However, because there is a lot of bad strategy out there,[vii] people often run with their thesis and hope for the best results.

After you’ve tested your thesis, start marking strategic choices and trade-offs about how to capture the opportunity you see. In Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works, A.J. Lafely and Roger L. Martin describe this as setting your ambition, deciding where to play, and determining how to win.[viii] This process is iterative where data about “where to play” and “how to win” helps refine your thesis and ambition and vice versa. After those steps, you then consider the specific activities and processes your business must do to capture the market opportunity. More specifically, you determine and optimize your business’ strategic capabilities.

In the end, you will have a specific statement of what your enterprise will do. For example, let’s say we’re opening a new local healthy restaurant, our statement might sound like, “Our restaurant will capture 10% of the local $100M restaurant industry by targeting 18-45 year olds who predominantly work and live near downtown and are looking to lose or maintain good weight by eating fresh whole food meals sourced locally.” In that statement, you have a goal (10% of the local market), a target market & location (18-45 years in or near downtown), and an overview of the capabilities (local food sourcing, marketing to reach target demo, restaurant management, etc.). By doing this process repeatedly, you’ll start to develop a sense for who has a good strategy or not by simply listening to people talk about their business.

The Politics Part

In politics, framing the election is the equivalent of the business thesis. In framing an election, campaigns refine their worldview and develop language for talking about those views. “Framing is about getting language that fits your worldview. It’s not just language. The ideas are primary—and the language carries those ideas, evokes those ideas.”[ix] For me, election framing becomes the campaign’s dominant logic.

A good frame can serve a few purposes, such as focusing the campaign.[x] This ensures the campaign remains shielded from any outside distractions. Furthermore, good framing turns individual policy positions into a cohesive plan, which simplifies the campaign for the voter.[xi] Lastly, a strong frame can invite opponents to do what I’ll refer to as “conceding the frame.” Candidates can concede the framing for an entire election by using language and/or creating a policy agenda that falls into their opponent’s frame.[xii] Conceding the frame can be fatal to campaigns. Like the business thesis, a frame should be vetted by data and political analysis. The frame must not be irrelevant, myopic, inflexible, or unpopular.

The New Deal is an example of a good frame. In two words, FDR effectively communicated that he would end the old policies and enact new ones to alleviate and end the Great Depression. When President Hoover opposed the New Deal, voters could easily ask themselves, “What does Hoover want? The Old Deal? I don’t want that.” A good, relevant, and persuasive frame can lay a strong foundation for a campaign.

After framing the election, campaigns make strategic choices and trade-offs. They’ll determine how many votes are needed to win, which voters to target, how to motivate their base, and which geographies are most important. The research behind these choices will also inform the frame and vice versa. These choices should be made bespoke for each election, but in Democratic politics, Triangulation is the default strategy.[xiii]

Triangulation is one of several potential strategies that politicians can use to advance their campaigns.[xiv] Triangulation’s goal is to neutralize opponents by solving their top priorities with solutions that will appease your political base and utilize ideas from both sides.[xv] This positions the campaign in the political middle and, theoretically, creates maximum support among the public. For example, Former President George W. Bush “was determined to take education and poverty away from the Democratic Party and make them, in part at least, Republican issues.”[xvi] President Bush, of course, won the election and passed the No Child Left Behind Act, a significant piece of education legislation, with bipartisan support.[xvii] President Clinton also used triangulation to a certain extent in his 1996 campaign.[xviii]

A campaign’s next step is to assess its strategic capabilities. As a reminder, capabilities are the activities and processes companies engage in to capture market opportunities. It is what an organization does from paying its bills, advertising, and beyond. Not all capabilities require top notch treatment, but those that are key to business or campaign success need to be the best. For campaigns specifically, strategic capabilities include, but aren’t limited to, the ground game (e.g., get out the vote, volunteering, door knocking, etc.), advertising, fundraising, media operations, and data gathering & analysis.

Therefore, your translation from business to political campaign strategy will look like this:

With that established, let’s examine where Democrats fail often.

Democrats Fail to Frame:

Some campaigns are flawed from the start. If campaigns fail to have a strong frame, then voters will find it difficult to connect with candidates and elect them. Frameless campaigns are more prone to character attacks and distractions than a well-framed and focused campaign. Without framing, voters might conclude there is no distinction between candidates despite clear policy differences. Democrats will consistently run into Republican opponents with strong frames because Republicans generally have a better understanding of their framing.[xix] Even the Republican’s most ridiculous sounding frames will be more likely to succeed over any frameless Democratic campaign.

One indicator of a frameless campaign occurs when the overarching logic is summed up as, “<Insert Name Here> should be <Insert Office Here> because they’re <Insert Name Here>.” In addition to circular reasoning, this campaign rationale becomes more about the candidate’s ambitions or career than the voters. Former Secretary Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign is an example of this. Frames or lack thereof are often, but not always, captured in the campaign slogan. For Hillary, “Stronger Together” and “I’m with Her” were the main slogans. My initial reaction to those slogans is: “What is stronger together?”, “Why am I with her?”, and “What is she going to do for me exactly?” If you are a regular politico, you might say, “Hey, these answers are obvious. The American people are stronger together than apart. You’re with her because she’s not Trump at least.” But for the non-politicos, those answers aren’t obvious. Additionally, Hillary’s unfavorable ratings were high.[xx] A lot of people didn’t want to be with her. She also, fairly or unfairly, had numerous scandals during her campaign. Leaving a voter to wonder, “Is that what I’m getting with her?”

Compare this to former President Obama’s 2008 campaign slogans. “Change We Can Believe In” and “Change We Need” are very clear frames.[xxi] A voter can ask themselves “What am I getting when I vote for Obama?” and immediately think “Change.” Change can be a very persuasive frame that is simple, voter centric, and focused. Thus, when Republicans attacked Obama, the voters could weigh the relevance of those attacks against the benefits from the change. Obama’s frame also created a consistent logical structure for his policy agenda. Why is Obama going to cut taxes for the middle class, end the war in Iraq, and reform health insurance? Because these things need to change, and he’s bringing change. Hillary famously made fun of Obama’s framing in the primaries while offering no alternative framing and lost.[xxii] The late Sen. John McCain basically conceded the need for change by framing his candidacy around being a maverick[xxiii] and lost. Therefore, when you sum up and compare the two campaigns, with Hillary we got “Hillary Clinton should be President because she’s Hillary Clinton,” and with Obama we got, “Barack Obama should be President because he’ll bring change.” The big difference was losing in 2016 and winning in 2008.

Another frameless indicator is “issue of the week” or “slogan of the week” type campaigning. Obviously, this is not a literal weekly change, but a frequently changing frame signals a lack of framing. In 2004, then Sen. John Kerry jumped from slogan to slogan. He had no slogan in the primaries, to saying “Let America Be America Again”, to “Stronger at Home, Respected in the World”, to finally “A Stronger America” and “Wrong Choice, New Direction.”[xxiv] The last change happened very late in the election and right before the presidential debates.[xxv] How is a voter supposed to approach your campaign if it keeps changing what it is about? They can’t.

Another example of this (I’m seriously not trying to pick on Massachusetts Democrats) is Sen. Warren’s presidential campaign. Sen. Warren gained quite the reputation for having a policy for everything,[xxvi] but without an overarching frame to join them together, then what is her candidacy about? It becomes about just electing Elizabeth Warren president because she’s Elizabeth Warren and that wasn’t enough.

The Triangulation Trap:

As I mentioned above, Triangulation is the default Democratic strategy, and candidates make strategic decisions and trade-offs through that lens. At a high-level, this is backwards. The framing should drive the strategic choices and not the other way around. Instead, we get candidates who force the framing choices into the triangulation framework. This limits available frames and finding different ways to win. However, this logical inconsistency is a framing creation issue rather than a trap inherent to Triangulation.

The Triangulation Trap is walking the tightrope of bringing new policy solutions sourced from progressive and conservative ideas and outright conceding all election framing to the Republicans. Conceding an election’s frame to Republicans is basically a concession speech. When Democrats adopt Republican language and terms or re-orient campaigns too far to solve Republican priorities, they are essentially saying, “Republicans are correct about the most important issues, but Vote Democrat because we can solve those issues too.” That’s not leadership or compelling. In these cases, Democrats end up running as “Republican Lite” by offering a watered-down version of a Republican agenda or having a disproportionate focus on the political process, which often manifests as an overemphasis on bipartisanship.

Oddly enough, this is a lazy application of Triangulation. Dick Morris, who coined the term, and to be clear is NOT a role model[xxvii], instructs candidates to keep their base excited and apply Triangulation to high priority issues. Applied poorly or too broadly, Triangulation will alienate a candidate’s base and confuse the voter on the difference between Republicans and Democrats.

For example, watch this ad please:

The ad starts with former Rep. Tim Ryan talking about an exhausted majority, which is good framing if explored more. Then, he talks about having progressive and conservative solutions to America’s big problems, which is quintessential Triangulation. Then, Rep. Ryan discusses talking to people who we disagree with and how Ohio will be very important in that conversation for some unstated reason. Because of this conversation, we’ll boldly enter an age of possibility, reconciliation, and reform. Ryan doesn’t explain what policies we’ll enact in this new age, but at least we’ll be there. The viewer can tell Ryan is committed to this message because the ad has several different shots of him speaking in front of different crowds and locations. Ryan then notes that Republicans are voting for him (cool), which based on the sequencing in the ad is apparently the foundation of the campaign and why he’s going to win. Then, we all grabbed a seat on our couches on election night to watch Ryan lose by 7 points.[xxviii]

What did that ad say? Tim Ryan wants to be a U.S. Senator to talk to people he disagrees with, agree with Republicans sometimes, and represent exhausted people to some undefined end. By conceding that we need some conservative solutions, he falls into the Triangulation Trap by conceding the election frame. By obsessing on bipartisanship, Ryan’s not firing up either side. In fairness, he talks more about policy in other ads, but this ad was posted on the day before Election Day. Ryan’s closing argument is poor application of Triangulation, and he stepped into the Triangulation Trap. Now conversely, in my 2020 Georgia runoff prediction, I noted that now Sen. Jon Ossoff corrected similar mistakes, which set him up for victory. It was a good escape from the Triangulation Trap.

Campaign Capabilities:

Lastly, Democrats have a tendency of failing to optimize top strategic capabilities. And unlike the business world, politics is not afforded the luxury of constant iteration on those capabilities. Campaigns have one chance to get it right. Thus, strategic campaign capabilities must be top notch. However, Democrats tend to live with limitations. As mentioned above, a campaign can have many strategic capabilities, but for Democrats, I’m most concerned about data gathering and analysis. Data is the bedrock for voter targeting, fundraising, ground game, and message. Having bad or no data would be like flying a plane with no instruments, and Democrats do not have an advantage here.

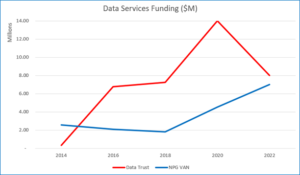

Historically, Democrats and Republicans had decentralized data operations. State parties would gather and add key details (e.g., donor, put sign in yard, etc.) to data.[xxix] They would then sell this data to candidates or only offer the data strategically to endorsed candidates.[xxx] As technology and data analytic methods change, the data becomes more valuable if brought together in a common format and joined with other commercially available data.[xxxi] Since then, Democrats and Republicans have launched various initiatives to bring their data together and to sell that data as a fundraising source.[xxxii] Based on my observation, the current competition is between the GOP’s Data Trust[xxxiii] and NPG VAN[xxxiv] as to which party has the data advantage. Quite frankly, I don’t like where the Democrats are right now.

Overall, the Data Trust is better funded. In the 2020 election cycle, Republicans spent $14,000,000 on the Data Trust[xxxv] while Democrats spent $4,545,030 on NPG VAN.[xxxvi] Underfunding a key strategic capability relative to competition is usually a bad omen. It is fair to think “but we won in 2020.” However, it’s worth noting that the election was closer than Democrats wanted and Republicans won every toss-up race for the U.S. House. Additionally, the Data Trust has been consistently better funded over the years:

(Source: OpenSecrets data[xxxvii])

Since 2014, the Data Trust has received $36M from the Republican Party compared to NPG VAN’s $18M. It is unclear from my research if NPG VAN makes up the difference from private contracts.

The Democratic Party is also less focused on data generally. In 2022, Democrats devoted 40% of their spending on media, which has a data component but is predominantly advertising.[xxxviii] Republicans outspent Democrats on fundraising, strategy, and research, which has heavier data components.[xxxix] Furthermore, the Data Trust remains in control by Republicans in a co-op style ownership structure.[xl] On the other hand, NPG VAN is now owned by a British private equity firm.[xli] The firm has already laid off over 100 people, which has raised serious questions about NPG VAN’s readiness for 2024.[xlii] Further muddying the waters, in 2019 the Democrats also started another data services business called the Democratic Data Exchange (DDx) to be their version of the Data Trust.[xliii] In DDx’s first two election cycles, the Democrats gave about $1M in funding.[xliv] The Republicans funded the Data Trust over 7x that amount in its first two election cycles.[xlv] With the limited funding, lack of control over a strategic capability, and higher priority on media spending, it is fair to say that the Democrats’ main focus is elsewhere.

Conclusion:

If there is a running theme in this post, it’s this: Democrats are not sufficiently strategic in their campaign design. Democrats need to nail the framing, the strategic choices and trade-offs, and strategic capabilities to give them the best shot to win. I once read somewhere a good campaign strategy takes 3 months to create and 30 seconds to explain. This suggests that deep thinking and analysis is at the core of winning competitive elections. I just can’t tell from the outside looking in whether that process happens consistently in the Democratic Party. Of course, there’s a lot more to campaigns winning and losing than the framework I laid out today (e.g., gerrymandering, voter suppression, candidate scandals, etc.), but these strategic factors mentioned above are squarely in the campaign’s control and will lead to more wins, if used to the fullest potential.

[i] https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2010/01/republican_scott_brown_wins_ke.html

[ii] See note i.

[iii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/02/11/democrats-underperformed-their-expectations-2020-thats-not-surprising-considering-where-country-is/

[iv] https://news.gallup.com/poll/116584/presidential-approval-ratings-bill-clinton.aspx

[v] https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/07/politics/campaign/baffled-in-loss-democrats-seek-road-forward.html

[vi] https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/elections/12-days-stunned-nation-how-hillary-clinton-lost-n794131

[vii] Rumelt, Richard P. Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters. Currency. 2011. Chapter 3.

[viii] Lafley, A.G. & Martin, Roger L. Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press. 2013.

[ix] Cite Don’t Think of an elephant pg 4

[x] The following is a bit of a summarization of the relevant portions of Lakoff, George. Don’t Think of an Elephant!: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate. Chelsea Green Publishing. 2004.

[xi] Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant!, pg. 29-33.

[xii] Lakoff, Don’t Think of an Elephant!, pg. 3.

[xiii] I’ve concluded that Triangulation is the default Democratic strategy because of how well it fits with the Democratic Party’s moderation in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which I write about in more detail in “What Is the Point of a Moderate Democrat?”. Given the continued hold on the presidential nomination and party leadership that moderate Democrats have, it is logical to think that Triangulation has been very influential in Democratic campaign thinking.

[xiv] By way of example see, Morris, Dick. Power Plays: Win or Lose – How History’s Great Political Leaders Play the Game. ReganBooks. 2002.

[xv] Stephanopoulous, George. All Too Human: A Political Education. Back Bay Books. 1999. Pg. 334-35. Morris, Power Plays, pg. 89-93.

[xvi] Morris, Power Plays, pg. 92.

[xvii] https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/no-child-left-behind-an-overview/2015/04

[xviii] See note xiv.

[xix] Lakoff, George. Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. The University of Chicago Press. 2016. Pg. 31.

[xx] https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/poll-clinton-unpopularity-high-par-trump/story?id=41752050

[xxi] https://www.politico.com/blogs/ben-smith/2008/08/a-changed-slogan-the-change-we-need-011288

[xxii] https://www.politico.com/story/2013/08/barack-obama-hillary-clinton-2008-campaign-095035

[xxiii] https://youtu.be/TmLVtU6fTPs

[xxiv] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2004-sep-20-na-kerry20-story.html ; https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/saffy_images/226/

[xxv] See note xxiv.

[xxvi] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/10/us/politics/elizabeth-warren-2020-policies-platform.html

[xxvii] Dick Morris, who is literally part of the Roy Cohn family tree, drew the ire of George Stephanopoulos while working for President Clinton in 1996 because of his demeanor and willingness to sacrifice Democratic priorities while also consulting for Republicans. Morris resigned from the 1996 Clinton campaign in scandal. He has spent the intervening years attacking the Clintons and making bad political predictions (link here), which led to Fox News firing him.

[xxviii] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/11/08/us/elections/results-ohio-us-senate.html

[xxix] https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2012/01/the-co-op-and-the-data-trust-the-dnc-and-rnc-get-into-the-data-mining-business.html

[xxx] See note xxix.

[xxxi] See note xxix.

[xxxii] See note xxix.

[xxxiii] https://thedatatrust.com/

[xxxiv] https://www.ngpvan.com/

[xxxv] https://www.opensecrets.org/political-parties/republican-party/RPC/2020/expenditures?t0-search=data

[xxxvi] https://www.opensecrets.org/political-parties/democratic-party/DPC/2020/expenditures?t0-search=VAN

[xxxvii] 2014 was the first election cycle for The Data Trust. I assume the dip in ’22 funding is related to it being only midterm year.

[xxxviii] https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2022/11/how-republicans-and-democrats-spent-their-money-during-2022-midterm-elections/

[xxxix] See note xxxviii.

[xl] See note xxix.

[xli] https://theintercept.com/2023/01/24/layoffs-democratic-party-ngp-van/

[xlii] See note xli.

[xliii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/powerpost/copying-the-gop-democrats-focus-on-data-exchange-with-dean-leading-the-charge/2020/05/30/781d6630-a1d7-11ea-b5c9-570a91917d8d_story.html

[xliv] OpenSecrets data

[xlv] Open Secrets data